Americans now have the least confidence in finding a new job since at least 2013, a period also known as the depths of the “jobless recovery” following the Great Recession. According to the latest August 2025 Survey of Consumer Expectations from the New York Federal Reserve, the perceived probability of securing a new job in case of job loss has dropped to 44.9%. That’s the lowest reading since the start of the series in June 2013. The decline was broad-based across age, education, and income groups, the New York Fed reported, “but it was most pronounced for those with at most a high school education.”

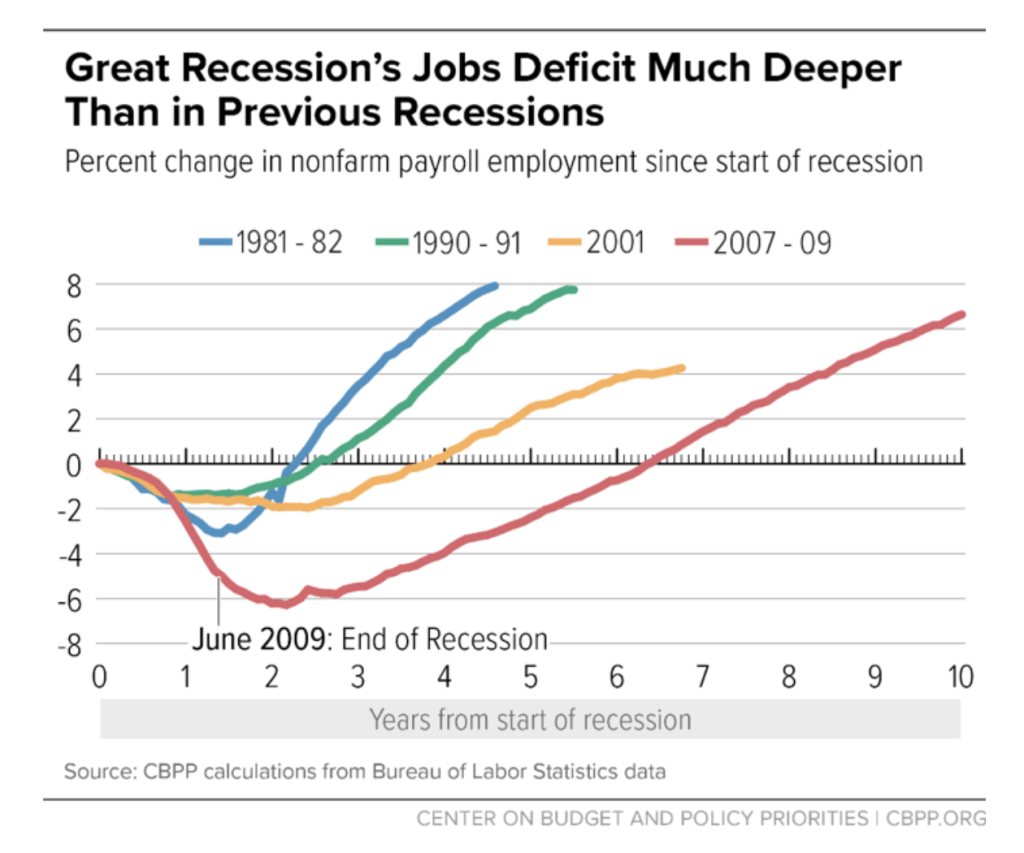

The term “jobless recovery” predates the Great Recession that began in 2008, but it took many years for the economy to recover all the jobs lost in the crash after the subprime mortgage bubble popped. At its peak, unemployment soared past 10% in late 2009, only dropping below 8% by 2013—more sluggish than prior recoveries. Employers slowly restored payrolls, but the jobs deficit from the recession was so vast that, even by mid-2014, the economy had merely regained the 8.7 million jobs it had lost since 2007. Many workers spent months, even years, looking for jobs, and long-term unemployment reached historic highs.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan think tank, explained the Great Recession created an unusually large and long-lasting “output gap,” between actual and potential GDP, which manifested in substantial excess unemployment and underemployment. It took until 2017 for this output gap to close, according to the Congressional Budget Office’s August 2018 Economic and Budget Outlook estimates—and even then the economy did not ever resume its potential GDP track from before the crash.

Even into 2017, millions of Americans who wanted jobs couldn’t find them, or could only get part-time work. Labor market “slack”—which also counts discouraged and underemployed workers—reached record highs, and the share of the population with a job fell to the mid-1980s levels.

Why so gloomy?

The New York Fed’s survey, which polls a rotating national panel of about 1,300 household heads, tracks inflation, price, labor market, and financial sentiment. Other findings were more moderate than the pessimism on future unemployment.

Earnings growth expectations dropped slightly to 2.5%, staying below the 12-month average and in a long-term range since 2021. The mean probability unemployment will be higher rose by 1.7 points to 39.1%, remaining above the annual average. Job loss fears ticked up to 14.5%, above the average, while the likelihood of voluntarily leaving a job fell to 18.9%, slightly below the average.

More respondents said they felt worse off compared to last year, and a smaller share reported a better financial situation, and expectations were more polarized for the future. A larger share of households are expecting a worse financial situation, while an equally larger share of households are expecting a better financial situation to come a year from now. Perhaps in another sign of polarization, a significant percentage (38.9%) expected stock prices to rise in the next year.

To be sure, the economy is in a much better place this year than it was in 2013. The past eight years of Trump and Biden economies were largely an expansion, albeit with an inflation wave that was unlike anything seen since the “inflation mountain” of the 1970s and ’80s. Unlike the jobless recovery of the 2010s, the U.S. economy gained back every job lost in the unprecedented layoff wave of the pandemic in remarkably few years, and then significantly outperformed other economies worldwide.

The doom and gloom among consumers is likely related to the concerning trend of low hiring that is increasingly becoming apparent from revisions by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The emergence of AI and its impact on the labor market is also hotly debated, but several studies indicate it is displacing some entry-level hiring.

Annual revisions by the BLS revealed an economy with “less momentum than previously understood,” Bill Adams, chief economist for Comerica Bank, said in a statement to Fortune. Adams noted 2024 was believed to be growing at a pace of 168,000 new jobs per month and 2025 at 75,000 per month, per previous data, but this had now been cut to 106,000 and 44,000, respectively.

“There was an outsize downward revision to employment in the information industry,” Adams said. “The revised data show more clearly that AI is automating away tech jobs.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

5 hours ago

1

5 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·