- Foreign investors may bring tariff-related claims to arbitration, arguing U.S. tariffs may be in violation of some international investment treaties, experts tell Fortune. The claims have never succeeded against the U.S., but tariffs are ‘effectively destroying’ some agricultural businesses, they say.

Foreign investors with business in the agriculture sector are considering bringing claims against the U.S. government as some believe tariffs have violated international investment treaties that promise them fair treatment.

International agriculture businesses with investments like distribution networks and subsidiaries in the U.S. are weathering tariffs, which have caused them to alter their business activities, renegotiate contracts with distributors and even threaten to price them out of the market, experts tell Fortune. In response to these produce tariffs, foreign investors are considering bringing claims against the U.S. under international investment treaties, which include a myriad of stipulations like fair and equitable treatment and protects against depriving investors from benefiting from their U.S.-based investments.

Produce imports on goods largely grown outside the U.S., including bananas, blueberries and avocados, totaled more $33 billion last year. Many large, internationally-based agriculture companies establish U.S. subsidiaries instead of selling directly to wholesalers, investing in machinery, workers, and a distribution network to sell its product. But tariffs have squeezed margins for these commodities, which has made U.S. portions of these ag businesses hard to sustain, Tiffany Comprés, founding partner and co-chair of international disputes at Pierson Ferdinand LLP, told Fortune.

“Fresh produce has had no tariffs since around the 90s,” Comprés said, adding that investments in a U.S. distribution network for fresh produce sellers were made under the expectation that tariffs would remain at zero. “Right now you are imposing tariffs, and it’s already a low margin business, so you’re effectively destroying the ability of that business to function.”

This is the claim that some foreign ag businesses are considering suing the U.S. government over, Comprés, who represents some foreign agriculture investors, said.

If foreign investors decide to follow through, they could begin the process by bringing a claim against the U.S. in an international arbitration tribunal, rather than a domestic court, alleging that tariffs violate the standards of treatment for investments outlined in international investment treaties. International investment treaty disputes are arbitrated under a third-party institution that employs attorneys who specialize in international law and have no particular ties to either party. None can be citizens of either country.

Although the USMCA agreement currently excludes tariffs for goods from the country’s largest trade partners in Mexico and Canada, imports from Latin American countries—including bananas and coffee, which the U.S. relies on to meet consumer demand—are facing steep tariffs, David Ortega, a food economist and professor at Michigan State University’s College of Agriculture & Natural Resources told Fortune.

“Brazil is the largest producer of coffee. They’re a major source of our coffee imports, and they’re currently facing 50% tariffs,” Ortega said. “So that’s raising the cost of product, the cost of importing the coffee into the US, and having very significant impacts on roasters here, but also on producers in Brazil who no longer have tariff-or-duty-free access to the US market.”

Though Brazil does not have an international investment treaty with the U.S., countries protected under the Central America-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) investment treaty like Guatemala and Honduras, which collectively export billions in produce to the U.S., may have a claim. Argentina and other countries under Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) also have protections that may be violated by tariffs, Comprés said.

Comprés said her clients are waiting for the Supreme Court’s ruling on the legality of tariffs before bringing any claims, and even then they will need to determine if their case is strong enough to bring before a tribunal.

“Investors want to assess their damages,” Comprés said. “They need to determine if it really makes sense for them.”

Comprés pointed out that there is a five-year window to bring a claim, and that foreign investors will want to make sure they have their “ducks lined up.”

“I would be shocked if we didn’t start to see (the claims) within the next five years,” Comprés said.

But, any potential claims under international investment treaties have an uphill battle.

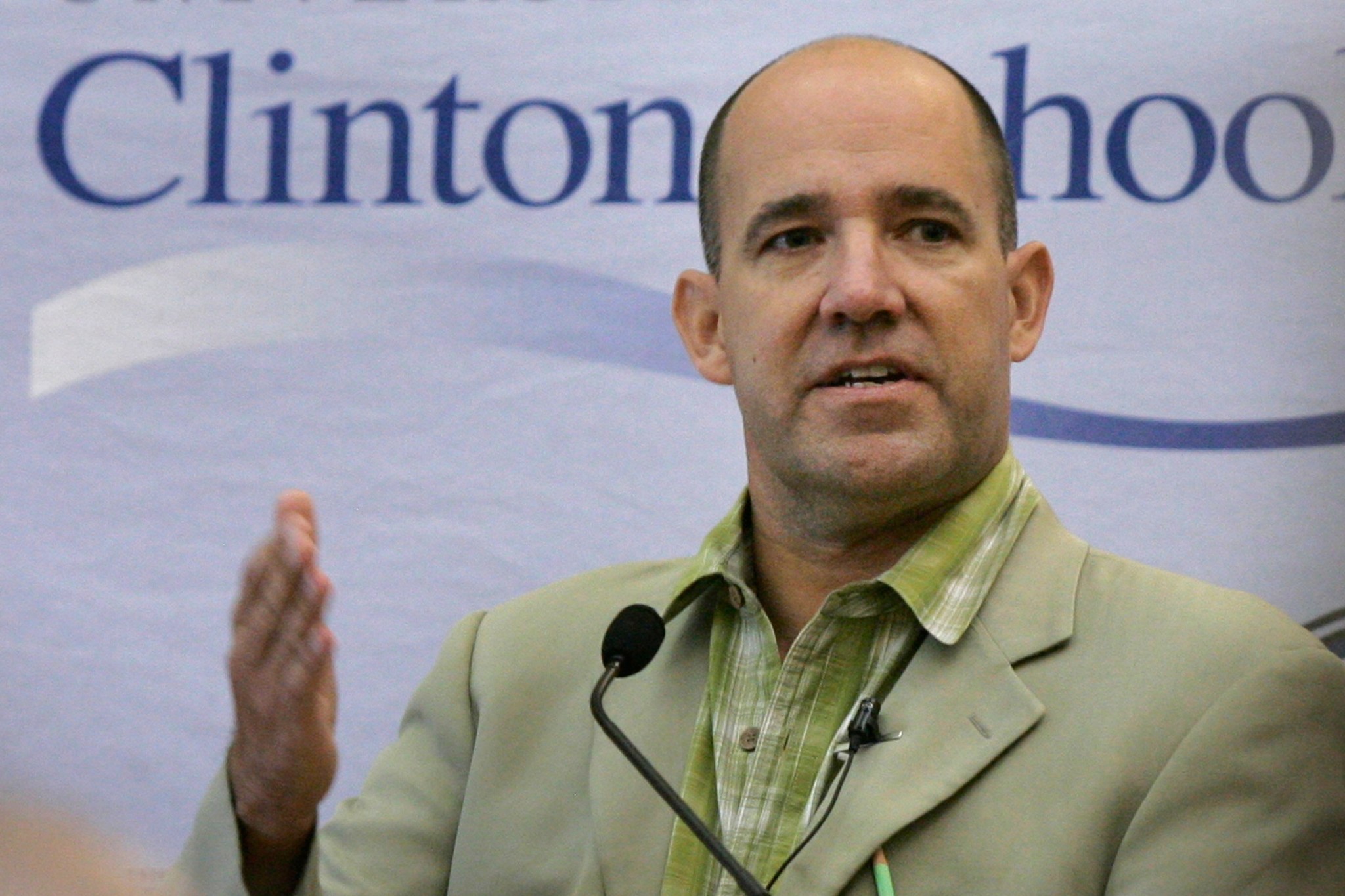

“The United States has never lost any investor-state dispute claims,” Robert Howse, professor of international law at the NYU School of Law, told Fortune.

Howse added that foreign investors bringing a claim would have to fit a very specific criteria, and wouldn’t be eligible for a claim if they solely sold produce to American wholesalers.

“You actually have an investment, a distribution network, a warehouse… those all are things that would count as investments in the United States,” Howse said. Then, the company would have to prove that its investments have been made largely worthless because of tariffs. But even then, Howse said the U.S. could argue tariffs don’t violate fair and equal treatment, as they reflect the country’s sovereignty over commercial matters—and commercial policy, including tariff policy, is part of the general regulatory environment that investors know can change.

“This is a fundamental aspect of President Trump’s agenda, even from when he was running for office the first time,” Howse said.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·