In Mumbai’s local trains, the ladies’ compartment is a paradox. It promises safety through separation, comfort through containment. It’s where strangers sit shoulder to shoulder, share recipes before names, or exchange sighs instead of stories. These quiet solidarities are the premise of Ladies Compartment, a group exhibition by Method (India), now on view at Galerie Melike Bilir in Hamburg, Germany.

Traindiaries | Photo Credit: Anushree Fadnavis

Beyond gendered train coaches

The show brings together six Indian women artists — Anushree Fadnavis, Avani Rai, Darshika Singh, Keerthana Kunnath, Krithika Sriram, and Shaheen Peer — each reflecting on gender, space, and resilience. Rooted in the hyperlocal image of Mumbai’s gender-segregated train compartment, the exhibition poses larger questions of how women move through the world and the spaces — physical, emotional, cultural — that define those movements.

“Most Europeans I spoke to had never encountered the idea of gendered train coaches,” says Sahil Arora, curator and founder of Method. “But that doesn’t mean women in Europe are completely safe. The compartment becomes a doorway to talk about what safety looks like, who gets access, and at what cost.” The show, part of India Week Hamburg 2025, marks Method’s first exhibition in Germany.

Sandra as a Hindu Goddess | Photo Credit: Keerthana Kunnath

Open to questions

While the premise of the exhibition draws from a recognisable Indian experience, its intent is not parochial. These are not works that merely illustrate a theme—they think through it, press against it, and resist neat conclusions. Each artist speaks in her own vocabulary of image, pigment, gesture, or breath.

Take Darshika Singh’s video piece, In A Single Thought. Built around rhythm and repetition, it quietly questions how women’s labour—especially physical, caregiving work —is rendered invisible by its very frequency. “Society’s expectation of women’s productivity has a lot to do with how our gestures get naturalised,” says Singh. “But repetition can also be looked at anew. One way preserves order; the other breaks it.”

The idea that disruption doesn’t always need to be loud runs through the show. In a striking series of fading self-portraits, Krithika Sriram uses rose-petal pigment to create what she calls “a disappearing image” of the Dalit female body. The work deliberately turns away from the spectacle of caste violence. “This is not about gore,” she says. “It comes from someone looking at their own history with agency.”

In My Mother’s Saree | Photo Credit: Shaheen Peer

Sriram’s work invites viewers to question how we memorialise pain — and whether beauty dilutes or dignifies it. “I don’t think beauty softens the critique,” she says. “If it exists, it reflects my perspective, my right to represent my own body.”

Photographer Shaheen Peer takes a similar route of quiet defiance. Her faceless self-portraits, draped in fabric, speak through form, not identity. “We’re often more concerned with who is in the image than what the image is about,” she says. By omitting the face, she shifts the gaze — toward memory, material, posture, presence.

Panna | Photo Credit: Avani Rai

Shaped by artists

These subtle but deliberate gestures accumulate across the exhibition. Fadnavis’s decade-long photo archive of everyday life inside Mumbai’s trains builds an ethnography of kinship and solitude. Rai’s portraits of Punjabi women document the weight of land, grief, and belonging. They have a blurry quality to them, making the subject—a young girl of about 10—a figure of aspiration as she writes, stands, and looks at you sideways while laying on a bed of flowers. Kunnath’s photographs of Indian female bodybuilders destabilise the idea of strength as masculine, and femininity as small.

For Arora, the curatorial process was artist-first. “This wasn’t about illustrating a curatorial statement,” he says. “The artists shaped the show.” He acknowledges the persistent gender imbalance in the art world — why “women-only” shows still exist. “If representation was truly balanced, these categories wouldn’t be necessary,” he says.

Kuvalai | Photo Credit: Krithika Sriram

Beyond the gallery

The ladies compartment has long served as muse and metaphor across Indian cultural work. In the novel Ladies Coupé (2001), Anita Nair situates her protagonist’s reckoning with womanhood inside a train coach filled with fellow female passengers — each sharing stories that unravel domesticity, duty, and desire. Photojournalist Shuchi Kapoor’s Rush Hour Sisterhood captures black-and-white portraits of Mumbai’s commuting women in moments of exhaustion, care, and camaraderie. The feminist zine Zero Tolerance by Bombay Underground (2007) visually mapped the compartment as both sanctuary and surveillance space, layering protest drawings with anonymous testimonies. In Nishtha Jain’s documentary, City of Photos, the train appears briefly but meaningfully, a passage between self-imaging and social invisibility. Meena Kandasamy’s poetry in Ms Militancy (2010) echoes the defiant solitude often felt in gendered public zones, while Niyati Patel’s spoken-word chapbook Commute Confessions uses fragments of overheard speech to archive a queer, caste-aware mapping of everyday intimacy in transit.

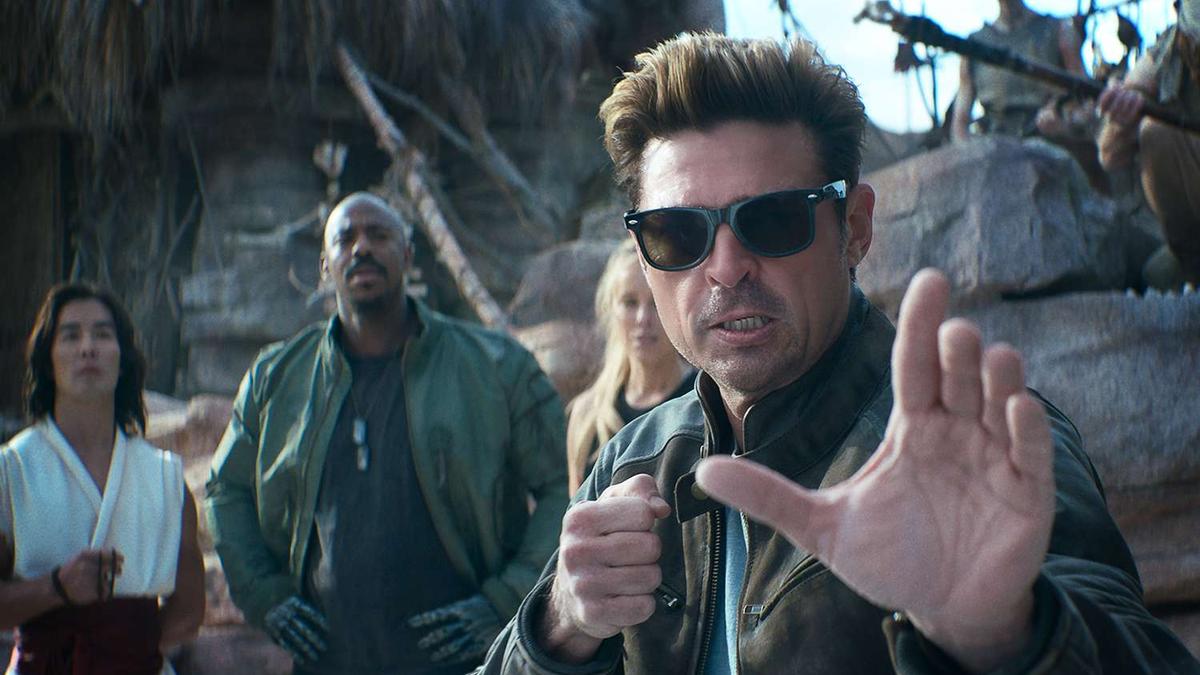

#traindiaries | Photo Credit: Anushree Fadnavis

No grand claims

The show doesn’t offer any easy takeaways. There are no declarations of revolution, no grand claims of feminist triumph. Instead, Ladies Compartment focuses on what is often overlooked — gesture, routine, and the quiet strength of repetition. It asks: when does a boundary protect, and when does it confine?

In Mumbai, women in the ladies’ compartment know each other by their train stops, silences, and the weight they carry — long before they know names or professions. Perhaps that’s the real offering here: a glimpse into how women learn to share space—unequally, gently, strategically —and the kinds of care, strength, and camaraderie built along the way.

The exhibition is on view till July 20 at Galerie Melike Bilir in Hamburg, Germany.

The essayist and educator writes on design and culture.

4 hours ago

1

4 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·