For more than two decades, AriZona’s iconic 99-cent iced tea has shrugged off pandemics, recessions, and supply shocks. Now, President Donald Trump’s new 50% aluminum tariffs could finally crack its unshakable price tag.

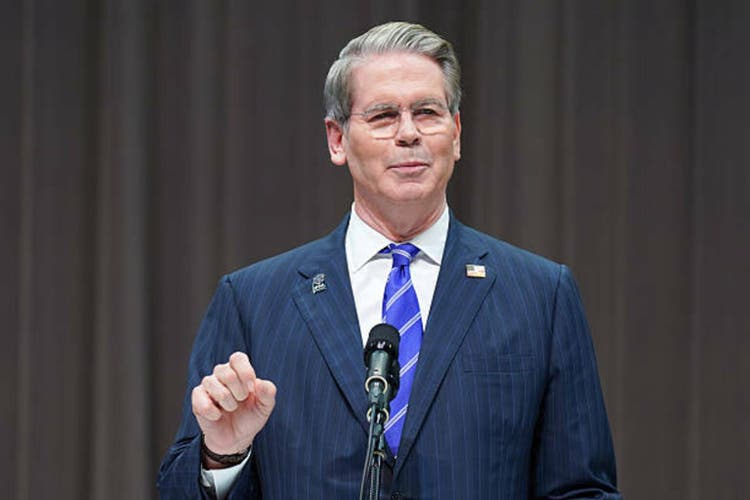

AriZona Iced Tea uses about 100 million pounds of aluminum for its signature cans, about 20% of which comes from Canada. Founder and chairman Don Vultaggio told the New York Times that unless Trump strikes a deal to lower the new aluminum levy with Canada, the company may be forced to raise prices.

“I hate even the thought of it,” Vultaggio told The Times. “It would be a hell of a shame after 30-plus years.”

The founder has made headlines for refusing to hike the price of his tea, even as inflation drives the prices of all other goods up. If Vultaggio adjusted the price of AriZona iced tea to match rising input costs, the tea would cost $1.99 today. Yet, the billionaire didn’t see a point.

“We’re successful. We’re debt-free. We own everything. Why?,” Vultaggio said in an interview with Today in June. “Why have people who are having a hard time paying their rent have to pay more for our drink?”

Vultaggio has tried other workarounds to save money on aluminum, including downsizing the can from 23 ounces to 22 ounces. Even that decision weighed on him.

Now, the founder worries the price of aluminum, which he said has “dramatically bumped up” because of the tariffs, might be the final blow to the 99-cent cans.

A test case for U.S. manufacturing

AriZona’s predicament could be a test case for what happens when a domestic manufacturer—one that’s nearly fully vertically integrated, even owning the railroad tracks its trains use to ship sugar daily—gets punished for importing some of its materials.

PNC’s Chief Economist Augustine Faucher told Fortune he thought the aluminum tariffs were unnecessary and inefficient.

Canada, which has access to abundant and inexpensive hydroelectric power, is one of the world’s leaders in aluminum production. Given the higher input costs of making aluminum in the U.S., importing it will always be cheaper than producing it domestically, he said.

“It’s going to be difficult to completely avoid tariffs, and that’s likely to contribute to higher consumer inflation in the near term as these companies pass along some of their higher input prices,” he said.

Faucher said companies like AriZona have few ways to blunt the impact. Unlike industries with slow turnover, which can stock up on inventory before the tariffs hit, beverage makers move product quickly. That means the aluminum tariffs will immediately hit the company’s bottom line.

All the price pain comes with very little gain, Faucher noted. Companies like AriZona, which imports some aluminum but produces the rest of the product domestically, might decide to just package the product overseas to avoid the duty.

“The idea is to help American manufacturers, but this hurts American manufacturers who use these types of imported inputs,” Faucher said.

The economist said he doesn’t see a need for the United States to have a strong domestic aluminum industry at all.

“It makes sense over the long-run to specialize in areas where the United States does well,” Faucher said. “But given the energy costs associated with aluminum production and getting bauxite and all that kind of stuff, it just doesn’t make sense for the industry to be located in the United States.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·