In the heart of Somerville, Massachusetts—a hipster enclave outside Boston—a group of Gen Z tech prodigies is flipping the script on government infrastructure.

They’re a team of twentysomethings operating on “996” schedules (that’s 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week), regularly pulling long nights and early mornings. But what really fuels them isn’t just competitive paychecks or bootstrapping their successful startup on the way to a $14 million series A. Instead, it’s a passion for transforming the world of “govtech” and redefining how governments manage and upgrade critical assets like roads and sidewalks.

According to financial documents reviewed by Fortune, their company Cyvl, co-founded by Daniel Pelaez, Noah Budris and Noah Parker when they were all just 21 years old, has reached millions in annual revenue. It’s growing, too, into a staff of roughly 30 employees. The punishing pace remains for founders, engineering leads, and new hires alike, but they have energy to spare. The average age at Cyvl is 26 or 27, hovering around the age of its founders, according to Pelaez, who still serves as the CEO. (Pelaez said they’ve hired some more experienced people as they’ve grown, nodding to the current VP of sales, VP of products and head of government relations.)

In interviews with Fortune, Pelaez and senior software engineer John Pignato described a startup with a competitive drive, fueled by seeing peers do impressive things at close range. “We’re a team of problem solvers,” said Pignato. “I have trouble putting down problems that aren’t solved.” He said he welcomes the long hours and sees it setting him up to become a founder himself someday.

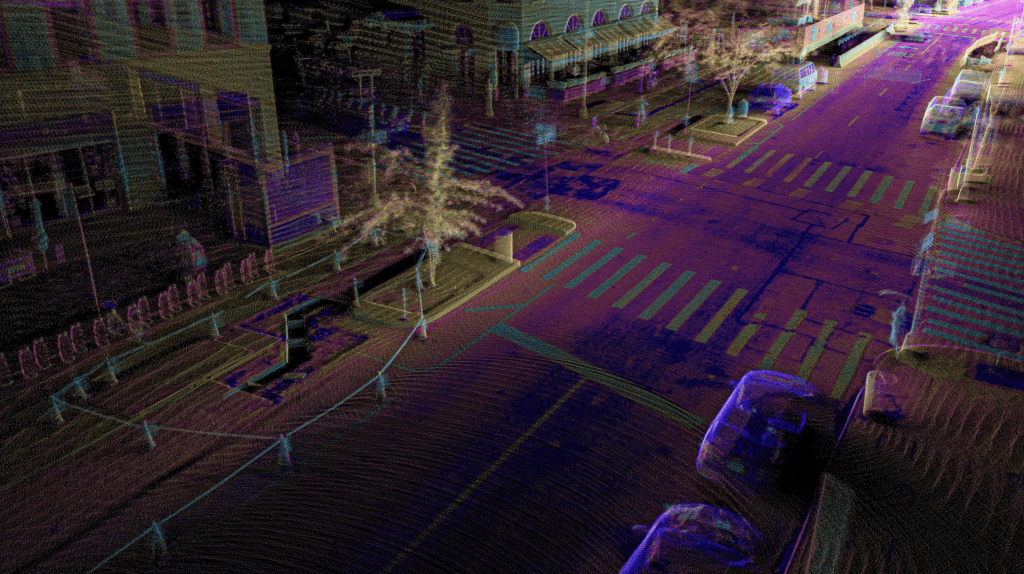

The life of a Cyvl engineer.

The life of a Cyvl engineer.”Here, Daniel’s like, a year, two years older than me, and he’s doing all these impressive things,” Pignato said. “And the other founders as well … they’re in here early. They’re doing great things.” He said it was “really inspiring to me to see someone really my age, that I can relate to, doing a lot of these big things themselves.” Of the collective work ethic, he allowed, “maybe it’s a flaw,” sharing that the whole team was at the office “very late the last three nights trying to solve a problem,” but they feel they just need to finish the work they start. “Everyone feels that way.”

Full disclosure: the author grew up in Massachusetts in the waning days of the Boston Celtics basketball dynasty of the early 1990s and shared that this description of civic-minded, gritty, hard-working young technies sounds like a well-drilled sports team. When asked about this comparison, Pignato—who was wearing a green shirt at the time—acknowledged that he’s aware of the franchise’s hard-working reputation. “Yeah, I’m a Celtics fan, so I relate to it. I don’t know if I see myself in that, but … that’s what I aspire to be.”

From splitting wood to filling potholes

The story starts in Oxford, a small town in southwest Connecticut, not far from New Haven, with Pelaez home from his freshman year of studying electrical engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in central Massachusetts. He told Fortune that he needed a job. He said he “didn’t have a cool internship” like his classmates, but he thought he could do something physical since he grew up working with his hands, including chopping wood for his old New England house that needed fuel for its wood-burning stove. “My grandpa was splitting wood in in his backyard in Oxford until pretty much the day he died.”

Pelaez said his parents flagged a help-wanted ad in the newspaper for the Southbury Public Works road crew. He recalled making a phone call and coming away with a job that day. “They said, ‘Sure, come in Monday, you gotta be in at 6 am.’” He said he was stunned by what he found. “There wasn’t much of a job description, it was just: get a pickup truck at 6 a.m. every day, drive around, find things that are broken, go home [and] do the same thing the next day … there was really no method to the madness.”

Pelaez said he asked his road-crew foreman, Jim, how they prioritized projects and heard back: “this is just how we run the town, we don’t have any information on the potholes, around the broken signs, around the trees that need to be cut, we just rely on people calling in or we need to drive around and find things.” Jim pulled out “huge three-ring white binders” and explained that they had paid “an arm and a leg” to a civil engineering firm for an audit and inventory of every road and sidewalk, and it was out of date after one harsh New England winter. Pelaez remembers thinking there had to be a better way to do this, since paving roads is often a town’s largest line item, but “we’re just sort of winging it, which I thought was nuts. I thought it was insane.”

‘They can’t be the only one with this problem’

When Pelaez went back to school, he said he started learning about cutting-edge technologies like LiDAR (light detection and ranging, a type of laser-mapping), robotics, and how both work to propel self-driving cars. He said he thought the same technology could actually be applied to government works. “You don’t see public works and technology or innovation ever in the same sentence and that was the first realization, like, ‘Wow, I actually think we could do something to help out Jim and the Southbury Public Works road crew. And in my mind I was thinking, they can’t be the only one with this problem.”

Cyvl maps out roads around the country with cutting-edge technology.

Cyvl maps out roads around the country with cutting-edge technology.During the 2019 Christmas break from his junior year at WPI, Pelaez said, he visited Jim again with his friends, both named Noah. He described what became his first ever “customer discovery interview” and recalled meeting with 30 public works departments through February 2020, just before the Covid pandemic outbreak. “It was the classic, like, we’d skip class in the morning … and we’d just drive to, like, Stowe (Vermont) public works, Harvard (Massachusetts) public works, we spoke with Worcester’s public works department at 6 a.m. because these guys get in so early.”

Pelaez said they learned in their first year that “this problem was consistent, it was a big problem, and this technology that we learned about in undergrad for self-driving cars and robotics, it really could be applied.” He also remembered a quote about technological innovation, that when you see something changing or growing exponentially, including exponential decreases in price, “pay attention to that.” He said that LiDAR sensors went from selling for $200,000 apiece, down to $100,000, down to just $5,000 when he graduated. Pelaez and the two Noahs said to themselves, “Look, I think we could use this tech for public works for governments,” realizing how “horribly inefficient” it was being done nationwide. “Every town and city in America struggles with this exact same problem.”

A sensor product that’s gotten a big AI boost

Cyvl’s flagship product is deceptively simple: a plug-and-play sensor kit shipped to city governments, installed on local vehicles, and used to scan every street, sidewalk, sign, and tree while public workers go about their daily routines. The collected data feeds into Cyvl’s Infrastructure Intelligence Platform, where proprietary AI algorithms assess conditions down to the smallest crack or sign of deficiency. Cyvl generates comprehensive, prioritized reports and actionable maintenance plans—turning what’s typically a months-long, costly manual process into an automated review accessible much faster. Governments working with Cyvl routinely see budgets stretch further, sometimes paving four times the mileage with better data and planning.

The numbers are impressive. Cyvl says it has partnered with over 400 municipalities and completed hundreds of government projects—ranging from New England’s largest cities to tiny towns hundreds of miles away in the southeast. Active clients now number over 100, Cyvl disclosed.

Pignato described to Fortune how he’s seen the business get another boost with rapid AI adoption. “Daniel was the one who put his foot down” in December 2024, saying they had to change the way they were working. Explaining how this had rapidly changed the company already, Pignato said that “for the longest time, we were building one product, which is that sensor that mounts on top of the car,” but AI has transformed this so that they can prototype products before physically building them, and they are getting feedback on tech performance in “minutes instead of months.” AI tools are not replacing engineers, Pignato added, they’re “removing the grunt work around producing a lot of these reports.”

Pignato shared a scene from a recent consult with a rival company that wanted advice on how to bring AI into its engineering workflow, and an awkward generational mismatch. “It was pretty funny when a lot of these, like, older guys towards the end of their career, gray hair, got on the call, and the camera turned on [to find] 26-year-olds on the other end, you definitely see the shock on their face for a little bit.” Pignato added that more and more people are reaching out from an engineering perspective, because Cyvl has shipped three or four products already this year, “which is breakneck speed.”

Life in the ‘996’ lane

Pelaez described the price that he’s paying to see Cyvl succeed. “I don’t think anyone starting their own company that expects it to be a high-growth startup should expect to work 40 hours or less. I just really don’t think that’s possible, you’re gonna have to work so freaking hard.” He described the long hours as he and the two Noahs ramped up in the early days. “For like an entire year, we did not sleep,” he said, describing marathon code-writing sessions, seven days a week for two years straight. “That was pretty crazy and, like, I’m sure we got close to burning ourselves out.”

Pelaez said they’ve learned that it’s “important to take some time for yourself” but that he also couldn’t recall the last proper vacation he’d taken. “I’ll do, sometimes, some weekend trips. I like to go camping up in New Hampshire, Vermont or Maine.” When asked about the “996” phrase, Pelaez said he’s familiar with it and it rings true. “I’ve now been trying to take one day a week just to, like, wrap up earlier and maybe [get] a workout in or maybe cook a meal myself.”

When asked about the difficult hiring climate for the rest of his generation, with Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell even acknowledging that “kids coming out of college and younger people, minorities, are having a hard time finding jobs,” Pelaez said he’s not seeing that at his business.

“I think, honestly, while the job search has been hard for really entry-level across all industries,” Pelaez said, “in some ways I feel like we’re benefiting from it.” He said Cyvl is looking for “young talent that’s ripe to be developed and super-hard workers is what we need to keep the energy high and new ideas flowing, so that’s been working out for us, honestly.” Adding that “the talent pool in Boston is awesome,” Pelaez said that he’s been loyal to his alma mater, hiring up a lot of WPI grads. “I feel like I’m getting old, but yeah, we continuously find awesome [talent], the brightest minds of kids graduating college and we continue to hire really strong.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

4 hours ago

3

4 hours ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·