In the world of cinema, where political narratives often dominate the landscape, filmmaker Edgar Baghdasaryan focuses on the deeply personal and often bewildering experiences of the individual navigating tumultuous socio-historical shifts.

His film Yasha and Leonid Brezhnev that came out in 2024, was screened at the Bangalore International Film Festival (Biffes) 2025, and offers a unique window into the human condition during and after the Soviet era, a time when nations such as Armenia were governed by a centralised system that also sought control over artistic expression.

“Tragicomedy allows me to explore the themes I care about, such as an individual’s experience of losing their world and finding themselves in a new reality they weren’t ready for,” Edgar said on the sidelines of BIFFes

Sign of the times

The Soviet era presented significant challenges for artists, who often faced pressure to conform to the party line, which mandated depicting the worker as a socialist hero and ensuring that any representation of social life, including religion, aligned with the official aesthetic.

A still from Yasha and Leonid Brezhnev by Armenian filmmaker Edgar Baghdasaryan | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Filmmakers during the Soviet era responded to these constraints in varied ways. Filmmakers Sergei Parajanov and Andrey Tarkovsky were celebrated for their resistance to this mandated aesthetic. They sought to revive symbolisms associated with a strand of pre-revolutionary Russian intellectual thought which sought an “end of history” — and the beginning of a new ideal world — through a Judaeo-Christian apocalypse. Literary figures like Maxim Gorky in their writerly evolution toyed with the idea of building a new godlike figure.

Parajanov, along with Tarkovsky, employed an avant-garde, lyrical approach characterised by dreamlike imagery, a painterly sense of lighting and composition, and a passion for folk and Christian motifs. Their use of symbolist imagery was often esoteric and ambiguous from the party’s perspective, leading to censorship and some of their films being shelved for years, partly due to their religious content.

Edgar chose a different route for Yasha and Leonid Brezhnev — tragicomedy. “Parajanov refused to conform to socialist realism, the official party aesthetic; what he did was artistically incredible,” he says. However, Edgar clarifies his own artistic motivations. “While Parajanov’s approach was a form of resistance, my goal is not to justify or critique politics; my goals are meta-political. I’m interested exclusively in the human factor.”

Time portal

The protagonist, Yasha, embodies this experience. He hallucinates ‘buddy’ interactions with figures such as former Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. Edgar sees Yasha representing a whole generation, who with the collapse of the Soviet Union, suddenly lost their sense of life’s meaning and found themselves adrift.

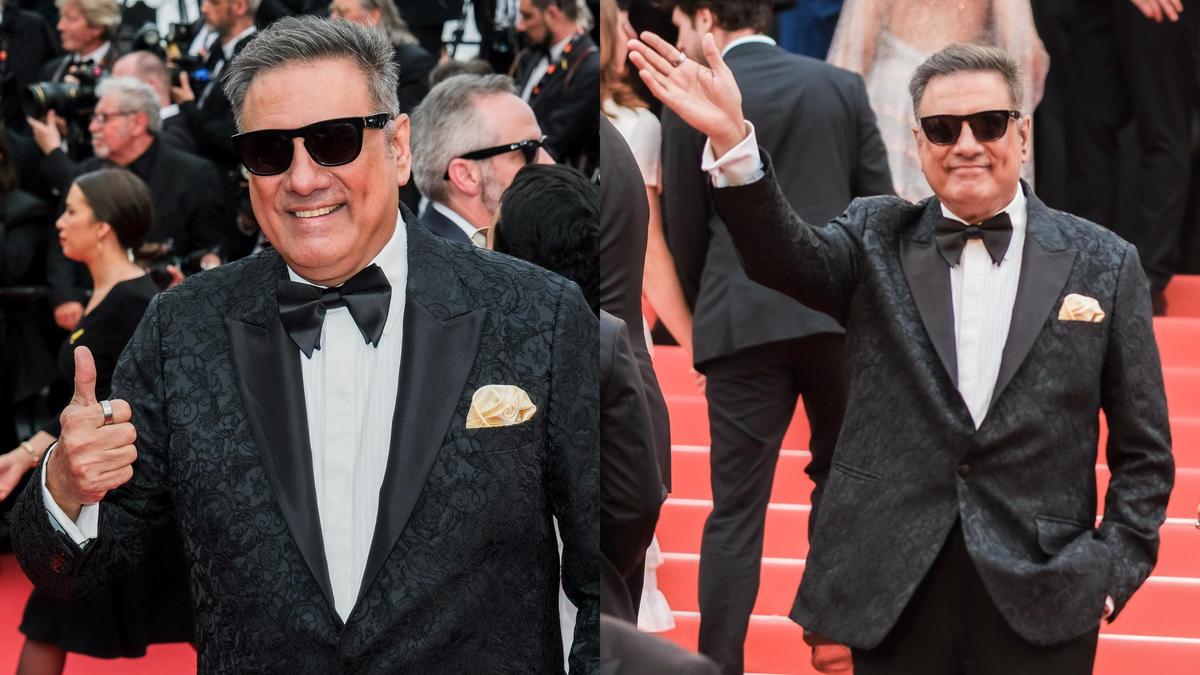

Armenian filmmaker Edgar Baghdasaryan | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

The 61-year-old filmmaker delves into the complex relationship between the present and the past, suggesting that individuals often look to the past for answers to current problems. He says much of what constitutes us as individuals have roots in the past, and he sees these roots as apolitical — in things like tastes, smells, joys, insults, first love, and one’s first kiss. “All the answers stem from our experience of things in the past. It is the basis of everything that comes after.”

Yet, the link between the present and the past is not logical; it is even absurd as with the case of Yasha’s hallucinations. This evidently escapist strategy, Edgar notes, is not unique to the older generation, as “the younger generation too is escaping into the digital universe”.

Yasha’s job as an operator in a municipal waste reprocessing unit evokes a metaphoric lingering stench. “That stench attaches itself to something and is impossible to banish. It is a cruel metaphor applied to those who wildly accuse the previous generation for all the current ills of society.”

While present generations may be justified in making such a charge in the context of extremist regimes of the past, Edgar argues that the era of Leonid Brezhnev, despite many idiosyncrasies, did not represent an extreme authoritarianism.

A still from Yasha and Leonid Brezhnev by Armenian filmmaker Edgar Baghdasaryan | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Edgar trusts in the essence of the individual spirit. “While biochemistry makes us all the same, it is the individual spirit that makes each person unique.”

Belief system

According to Edgar, true art must provoke “inquiry into the universal moral law as it can generate true happiness. Art helps you live and not just exist,” he says, adding that in contemporary Armenia, artists must “believe in the possibility of miracles, engage with hope and aim through art to make the world a better place”.

Even his musical choices reflect his aesthetic. “As a rule I seek to weave music into the fabric of the narrative and not insert it as pastiche. I look for organic reasons for doing this.”

The eclectic choices of music in Yasha, such as the Serbian song about Kosovo, are intentional, resonating with Armenia’s own Karabakh issue. However, he says, from another perspective, “the musical interludes and scenes are a pointer to what Yasha had been deprived of in real life — good food and drink, the company of beautiful women, and visits to exotic places, which were routine for the leaders with whom he now jostles in his altered reality. Yasha exults like Alice does in Wonderland — it is a land he doesn’t want to leave.”

Summing up on art’s purpose and his own legacy, Edgar says, ”If my films can make even one viewer question the reduction of life to mere transactions or help them get a glimpse of the sacred in the mundane, that is legacy enough. Parajanov taught me through his work, The Colour of Pomegranates, that beauty and pain are inseparable. And that it is only art that can act as antidote to numbness.”

Published - May 21, 2025 12:34 pm IST

6 hours ago

1

6 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·